- Home

- Galadrielle Allman

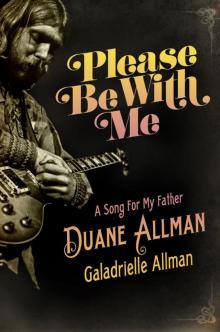

Please Be with Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman Page 7

Please Be with Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman Read online

Page 7

The new house felt tropical, with cool, speckled terrazzo floors. The boys would still share a bedroom, but they’d have their own bathroom tiled in blue. She bought new beds and dressers, and three tall stools for the kitchen’s built-in breakfast bar. A couch was beyond her budget, so she made big floor cushions and arranged them in front of a television cart. A wall sculpture of the Three Musketeers with plumed hats, knee britches, and swords raised in mutual salute hung in the living room. Duane pried the blades out of the carved hands and fenced with Gregg, clanking and jabbing, until one sword broke. They carefully folded a piece of gold paper to replace it and you could hardly tell.

Jerry found a new job at an upscale restaurant called the Bali. She kept the books, redesigned menus, and ordered all the produce and supplies, cutting their costs significantly. The owner came to depend on her completely. Her days lasted ten hours or more, and she worked seven days a week. Most nights, the boys were unsupervised and they learned to heat frozen pizzas and graze on snacks from the cupboards. Duane had a phone number where Jerry could always be reached. When she did find time to make late suppers long after dark, she unwound with whisky while she cooked. No one could argue with that; she had earned it.

My granny still lives in the house she had built in 1959. When I was a baby, I sat up for the first time in her big backyard, pulling myself up with a handful of grass while she watched from the kitchen window. I napped on the twin bed where my father used to sleep and sat on the sofa where he did homework and taught himself to play guitar. In the bedroom, two large windows let in pale light. On a recent visit, while falling asleep in their childhood bedroom, I realized that my father stared out these windows as he fell asleep every night. He heard the same suggestion of the ocean’s pulse when the wind shifted and stared at the cracks in this ceiling. He was everywhere I looked. The faint hum of my thoughts became a stronger buzz that shot forward with a loud and sudden growl. A motorcycle gunned its engine down the street outside as if driven straight from my mind and headed east over the waterway, and into the night.

Daytona was full of distractions, and Duane found it hard to care about school. He was sassy in class and cracked jokes. He pulled pranks like gluing down rulers and protractors to the table in shop class, and even once locked his teacher in the tool cage. He brought in comics and read them in the bathroom, counting down to three o’clock. At the sound of the final bell, he and some neighborhood boys would ride bikes back to Duane and Gregg’s house to watch TV, propped on pillows scattered on the woven grass rug. The boys called themselves a gang and buried a secret time capsule in McElroy Park. They carved their names in wet cement around the base of the new basketball hoop and played football on the lawn of an empty house nearby. Duane was a ferocious fullback, shoving the defensive line out of his way, always unafraid and quick on his feet.

The gang chased one another on their bikes to hotel pools, and walked casually through the fences, impersonating tourists from Tennessee with their towels around their necks, and went swimming. They spent whole afternoons at the Castaway, the only local hotel with an Olympic-sized pool with a real high dive, and Duane’s new friend Larry Beck was the best diver around. He leaped off the platform headfirst and twisted his body before straightening out perfectly and barely breaking the water’s surface on impact with a little splash. It was a beautiful sight to see. Duane didn’t have Larry’s technique. He would throw his arms up over his head in a silent cheer, then jump in after him, feetfirst. Duane was skinny and awkward next to Larry, but he was proud of his friend’s skill and he’d slap his back and tell Larry he was the best.

A couple of blocks down the road, another neighbor’s house was right beside the Neptune Drive-In movie theater. They’d run an extra-long line for a speaker into his yard; the kids, sprawled on blankets, all turned toward the movie screen that glowed like a giant floating postcard in the sky.

Duane was unfailingly confident, always the leader of the pack, but as he got a bit older, he began to disappear for stretches of time. He felt so restless sometimes he walked as far as he could on the beach just to wear himself out, or he’d head to his favorite quiet spot on the river where their street ended. A dirt path led through trees to the water’s edge, a perfect place to sit and think. He’d pull off his shoes and dangle his bare feet in the water. Pelicans would dip down to fish, so close you could catch a whiff of how badly they smelled. The sky was huge above the low bridge, and scant homes lined the river. Sometimes he took a book and read until daylight gave out. Sometimes he just watched the world go by, trying to keep his mind as still as he could.

In the summer of 1960, their uncles Sam and David came to visit. It was a great thrill to see them, Sam a strapping, handsome man and David a slightly awkward teenager with wavy hair and glasses. They took the boys on fast car rides on the hard-packed sand, went to the boardwalk and rode every ride, and then ate steaks in a nice restaurant with their mama, all of them dressed to the nines. After a week or so, they carried Duane and Gregg back to Nashville, to visit Grandma Myrtle and give Jerry a break.

Summer days in Nashville were long and hard to fill. One lazy afternoon at Myrtle’s house, Gregg wandered across the street to look in on her neighbor, Jimmy Banes. Myrtle didn’t approve of Jimmy; she said he wasn’t quite right. He was harmless, but surely slow. Jimmy was painting his car with black house paint and a brush—headlights, chrome trim, and all. Gregg thought, Maybe he likes the way the wet paint shines. He walked quietly across the road to get a closer look and sat on the edge of Jimmy’s porch. He noticed an acoustic guitar leaning against the house.

“Hey, Jimmy, can you play that guitar?”

Jimmy smiled and nodded. He put down his brush and took up a seat beside Gregg and played a simple song. He wasn’t bad. Gregg thought, I could learn to do that if Jimmy can. Jimmy passed the guitar to Gregg and that was it: Gregg caught the fever.

This story is the answer to the question Gregg Allman has been asked hundreds of times: “When did you first know you wanted to play music?” I have read Gregg’s answer many times and I’ve heard him tell it. He sits back in his chair and laughs, his eyes skimming the floor, one hand smoothing his blond hair back into a ponytail. His accent grows a touch stronger as he describes the heat of the summer day, the paintbrush in Jimmy’s hand dripping black paint. The story has the symmetry and perfection of a creation myth, and it has been repeated and embellished by every reporter who ever greeted Gregg with a tape recorder. Sometimes, he describes Jimmy painting his car, and other times, Jimmy’s car is old and dusty, like it was once painted with house paint. Sometimes, Jimmy plays “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain” on a Silvertone and sometimes “Long Black Veil” on a Beltone, a real finger-bleeder with strings set high above the neck, and hard to play. Gregg is a great storyteller, funny and warm, and even if the details shift and change over time, when he describes Jimmy patiently showing him his first song, it’s magical to imagine that he can locate the exact moment he found his path.

And Duane’s moment? Gregg tells that story, too. The brothers went to see a rhythm-and-blues review at the Nashville Municipal Auditorium that same summer: Otis Redding, Jackie Wilson, and B. B. King all in one show. The crowd was segregated, with the black teens seated high above the stage on wooden benches in the balconies and white kids below in red velvet seats. Jackie Wilson, smiling and smooth, swayed and clapped in his sharp suit. Hot lights blazed above the stage and everyone rocked in their seats, all except Duane. Gregg says his big brother sat forward on the edge of his seat perfectly still, transfixed.

Otis’s band would glide through love songs, then build to a foot-stomping frenzy, horns synched together so tight and fine you had to shout back at them. Pulsing with the backbeat of the drums, Otis scatted out notes lightning-fast, jumping up and down on his toes, and when the whole band stopped on a dime and suddenly bowed in thanks, a whoop rose up from every mouth in the room.

Then B. B. King took the stage, his gleaming

guitar high around his neck. His band swung into action, taking off like a train building a rhythm. The perfect, clear tone of his electric guitar rose out above them all. B.B. sang with his eyes closed and his eyebrows raised in curved surprise, trading verses with his own guitar, singing for him with a voice pure, clean, and so cool. His hand, flashing a big gold ring, wrapped around the guitar’s neck and danced there, shivering and gliding over the strings, effortless, almost involuntarily. B.B. rocked from one foot to the other, nodding his head, sweat pouring over his face, punching the notes with precision, the space between each held like a breath. What he didn’t play was as important as what he did, and the way he made you wait almost hurt.

Gregg watched Duane staring at B. B. King’s hands with complete focus and astonishment. Gregg says he could almost see a decision forming on his brother’s face.

Duane leaned in to Gregg and said, “Bro, we got to get into this.”

Out with their young uncle David one afternoon, they noticed the greasers that were part of the local music scene that was in evidence everywhere they went. They had swooping hairstyles combed up and back in defiance of gravity and wore their combs in their back pockets in case of emergency. They dressed with every bit as much care as their girls, matching their pressed shirts to the cuffs of their socks. The boys watched how they walked and stood, with their shoulders square, but relaxed, too. They even saw the Everly Brothers shooting pool downtown once. The Everlys had a song on the charts, but when they were home in Nashville they still hung out like regular guys. They wore custom-made jeans with only one pocket in back and the legs pegged tight; real slick. Kids surrounded their pool table, standing at a respectful distance to watch them play. Cool just flowed from them. Duane and Gregg were impressed.

When the brothers went back to Daytona, they brought home a little Nashville style and swagger. They put metal taps on the toes of their shoes so you could hear them coming, click click click. They pegged their black pants tight from knee to ankle and wore them with white dress shirts and white socks. They swept their hair back from their foreheads and carried combs. They sure stood out at Longstreet School, slinking down the hallway like a couple of toughs. No one dressed like that at the beach, especially not kids so young. Everybody took notice.

Gregg followed through on the idea planted by Jimmy’s guitar and the thrill of the Nashville show. He decided that when he returned to Daytona, he would get a job and earn enough money to buy himself a guitar. He did it, too. Within a week he found an early morning paper route and was out riding through the neighborhood on his bicycle, tossing folded papers overhand onto porches while Duane slept.

On September 10, 1960, Gregg rode his bike across the bridge to the mainland to Sears on Beach Street and bought his first guitar. He would always remember that date. A new Silvertone acoustic guitar cost twenty-one dollars, and Gregg had earned exactly that and then quit his job. The salesman at Sears counted Gregg’s money and turned him away because he didn’t have change for sales tax. His mama had to drive him all the way back downtown to give that man his handful of coins.

That guitar was the best thing Gregg had ever owned and he’d bought it on his own, which made it even better. Duane heard Gregg make his way through a few real songs and asked, “What do we have here, Baybro?” with all the menace of the Big Bad Wolf. Gregg could see it was going to be hard to keep Duane’s hands off his new prize, so he showed him the few chords he knew and seethed in frustration when Duane wouldn’t pass the guitar back. Duane took it from Gregg as much to piss him off as to play it at first, but soon he couldn’t put it down. Gregg stayed by his side and listened, showing him things and learning from him, wondering how Duane took to it so fast. They passed Gregg’s guitar back and forth, playing and listening, their radio playing low on the nightstand between their beds. Music soon filled the space that had held games and friends the year before.

Duane rounded the tight turn into adolescence on a blue Harley-Davidson 135 given to him by his mother for his fourteenth birthday. It was freedom and power, as she well knew, and she hoped it would help him burn off some of the intensity that smoldered behind his perpetually pissed-off expression. She gave him his own acoustic guitar for Christmas a month later, in an effort to keep him away from the guitar Gregg had worked so hard to earn. Not only had Gregg remained committed to playing; he had also stepped out alone and played for an audience for the first time.

The Longstreet School cafeteria smelled like boiled hot dogs and dust. Gregg was onstage and his eighth-grade class was waiting for him to play. The two guys who promised to accompany him didn’t show up and he was so nervous to play alone, he almost backed out. Then a teacher offered to join him on drums, so Gregg decided to go ahead with it. He picked his way carefully through a few surf tunes, never looking up from his hands. Once he got going, he managed to forget his butterflies and focused on the shapes his fingers needed to make, and he thought it sounded pretty good. Everyone clapped and smiled when he finished and relief and pride washed over him. It felt great. Kids he didn’t even know came up to him and asked when he was going to play again.

When he got home from school, he told a kid who lived around the corner that he was going to be a star. The boy laughed at him, but Gregg wasn’t kidding. He didn’t want to let that good feeling go.

Duane didn’t go to school that day, so he missed the whole thing. He was ducking class all the time now. He’d take the school bus with Gregg in the mornings and then part ways with him to head to his “office”—Frank’s Pool Hall on Main Street. He walked past the magazine racks and front counter with a swagger. In the back room, he ran the tables like a pro, squaring his shoulders and leaning his hip against the felt bumpers, steady as a judge. He could seem arrogant and stubborn to some, the way he dominated a room, but kids followed him around and waited for him to say something worth repeating. Things seemed to happen around Duane, and if they weren’t happening, he made them happen. He told stories while shooting pool about getting pulled over for speeding and talking back to cops, and he claimed he drank booze right at the dinner table in front of his ma. The kids that gathered there late in the afternoon would just stare. When they lingered too long, hungry for his attention, he’d yell, “Get out of my face!” and stalk off to walk the beach.

When the sun got too hot to stand, he’d go home to drink the beer out of the fridge and cool off. There was plenty of time to chase the smell of his cigarettes out the back door before Mama and Gregg came home. Soon he wanted to drink more than she would buy, and he started boosting beer from the liquor store. One night he and his new buddy, an older kid named Jim Shepley, took a hacksaw to the locks on the coolers that sat outside the store and made off with almost twenty cases of beer. They buried a trash can full of ice in the backyard to store it all, their private stash. They never did get caught and it didn’t last as long as you’d think.

Duane rode his Harley-Davidson, the pride of his life, beside the ocean on the quiet end of the beach near home. He’d push the engine and really open it up and take off wailing into the wind. He felt the edge of fear as he picked up speed, but it never came any closer than the horizon line. The only thing that scared him was how little it all mattered: speed up or slow down, walk around, talk to folks, play some pool, meet a girl, lie in the dunes with a can or a bag, go home, sleep it off; just keep rolling.

He was trying new ways to get high. He drew in the icy chemical breeze that came up from the Testors glue at the bottom of a paper bag crumpled hard against his nose and mouth, and stopped his mind cold. Dumb stillness—a moment of pure emptiness overtook him, and Duane wanted it back as soon as it started to fill up again with the sound of his buddy’s laugh and the edges of every shitty thought that had been there before—how late it was and how his mama was going to be waiting, how his girl was waiting, too, and how hard it was just to steal a little time. So inhale again as deep as you can, kid, and here it comes again, the big buzzing nothing, the echo at the bottom of

a well.

Gregg couldn’t understand the changes he saw in his brother. Duane seemed compelled to cause trouble and push up against authority wherever he found it. Duane rolled in at dawn and got into his bed just as Gregg was waking up. Sometimes he’d tell Gregg about a party he’d been to, but mostly he told him to mind his business. Duane knew that Jerry could always get Gregg to tell her where he was. Sometimes Gregg went along and he could sort of keep up with the drinking and all, but Duane usually wanted to be with older kids, and it hurt Gregg to be left out even while they were in the same room.

One night, Duane went riding in a borrowed car with four boys from the neighborhood, speeding down the straight stretches of Peninsula Avenue, windows rolled down to the hot night and loud engine. They’d been drinking beer for hours and his head was spinning, his stomach was seizing up in the worst way, and he wanted out. They were headed to Tomoka State Park, but Duane didn’t want to go all the way out there. They were going to the middle of nowhere to look for the ghostly lights.

Since the turn of the century there had been mysterious sightings in the dense forest beside the river, a phenomenon called the Tomoka Lights. On the two-lane park road, thick branches of oak trees draped with Spanish moss blocked the light of the moon and darkness reigned. It was difficult to see the road ahead and drivers were left to navigate by instinct and guts. The road itself was humped like an animal’s back and fell off into shallow ditches on either side. Driving fast with your headlights out gave you the best chance to spot the inexplicable orbs glowing in blackness. Some saw small groups of lights dancing together among the trees, drifting above the ground and moving beside their cars as they drove. Others said a single menacing ball of light as bright as fire sped through their windshields like a living thing protecting its territory. The light blinded drivers in a flash that forced some of them off the road. Skeptics guessed the lights were reflections from distant headlights magnified by the long, straight stretch of road. Others said natural phosphorescence caused by swamp gas was the source, but witnesses said the lights were clearly supernatural—spectral and strange.

Please Be with Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman

Please Be with Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman